Home | Publications | South Carolina Community Capital Alliance Case Study

I. CDFI Partnership Genesis and Structure

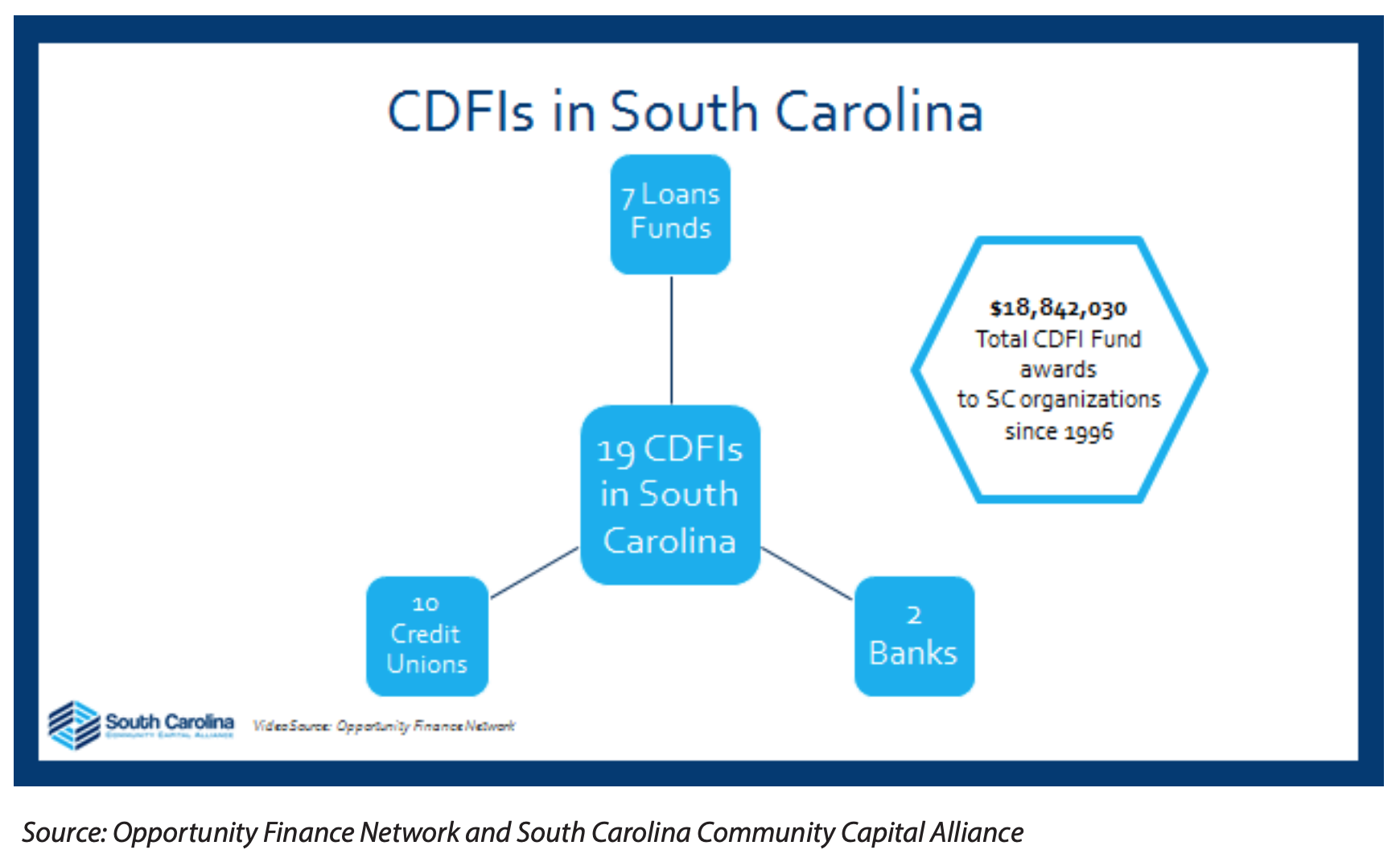

In the state of South Carolina, community development practitioners have a history of organizing to capitalize on opportunities to create practical solutions for the state’s low- and moderate- income communities in both urban and rural areas. The statewide Community Development Corporation (CDC) association was founded in 1994 by four CDCs. And, in 2000, the state General Assembly provided $10 million in grants, loans and tax credits to certified CDCs by enacting a Community Economic Development Act. The legislation required a state certification of entities as CDCs and CDFIs. Even though CDFIs may be certified by the U.S. Treasury, the state of South Carolina is separate and apart from that process. To that end, the state Department of Commerce contracted with the statewide CDC association to manage and train the organizations through a new certification program. Businesses, corporations, insurance companies, financial institutions and individual residents are eligible for a 33 percent credit against state tax liabilities for every dollar invested in or donated to certified CDCs and CDFIs. The state CDC association changed its name to the South Carolina Association of Community Economic Development (SCACED) to more closely align with similar references at a national level and to more closely align with the new legislation.

In 2011, a group of community development finance stakeholders came together to form a partnership called South Carolina Community Capital (SCCC). The goal of the stakeholders was to investigate whether or not the organizations could collaborate to attract capital and build additional finance capacity. The stakeholders included the Appalachian Development Corporation, CommunityWorks Carolina, Charleston LDC, the Mary Reynolds Babcock Foundation, the Michelin Development Corporation, South State Bank, SCACED, the South Carolina Community Loan Fund, the Support Center (now rebranded as the Carolina Small Business Development Fund) and Wells Fargo Bank. The first meetings were initiated by the CDFIs (CommunityWorks Carolina, South Carolina Community Loan Fund and The Support Center) and South State Bank, and later included the other stakeholders.

The goal of SCCC was certification as a CDFI by the U.S. Treasury and an application to the CDFI Bond Guarantee Program. Created as an independent 501(c)(3) organization, SCCC planned to raise and leverage capital, with a mission to work statewide to increase investments in the state’s low- to moderate-income communities and act as an aggregator for the state’s smaller CDFIs.

The CDFI Bond Guarantee Program was enacted through the U.S. Small Business Jobs Act of 2010 as a response to long-term, low-cost capital to “jump start community revitalization.” CDFIs positioned to act as a conduit to the broader CDFI community are able to apply to the CDFI Fund for authorization to issue bonds to be repaid over 30 years under a guarantee of the Secretary of the U.S. Treasury. Because the CDFI Bond Guarantee Program is intended to jump start larger commercial real estate projects and community facilities, and even municipal infrastructure, the scale proved too large for the newly created SCCC and the organization was not able to apply.

Another intermediary financing organization, the Southern Association for Finance Empowerment (S.A.F.E.), had been established in 2006 by the South Carolina Association of Community Development Corporations, now SCACED, to fill the need for statewide capital for CDCs. S.A.F.E. was also a CDFI, but because S.A.F.E. had not initiated intermediary or primary CDFI functions as a lender in the state, S.A.F.E. and SCCC agreed to a merger and the creation of South Carolina Community Capital Alliance (Alliance).

In March 2013, a process began to formalize the Alliance; S.A.F.E. formally merged with SCCC in 2015. SCACED provided fiscal administration for the organizations that fill a need for a network of CDFIs and community development organizations to educate the community as well as develop policy advocacy for the Community Development Tax Credit and potential future policy initiatives. Initially, each member organization made an investment to generate capacity for the new nonprofit. The Alliance quickly turned to engagement in public policy and capacity-building support to develop a network to support community investment and generate economic opportunities and growth. SCCC would raise, leverage and align capital for community economic development; identify gaps in community development financing; and facilitate co-lending opportunities between and among CDFIs for qualified projects.

The Alliance has a board, maintains a website and rotates leadership. The Alliance board of directors includes representatives from CDFIs and financial institutions. At present, the following organizations are represented on the organization’s board of directors: Bank of America, BB&T, Business Development Corporation of S.C., Charleston Local Development Corporation, CommunityWorks Carolina, PNC Bank, SCACED, SC Community Loan Fund, South State Bank, SunTrust Bank, The Innovate Fund, Carolina Small Business Development, TD Bank, Wells Fargo, First Citizens Bank, Benedict Allen Community Development Corporation, Self-Help, the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond and the New America Corporation. SCACED continues to provide fiscal management, incorporates the Alliance in its annual conference and provides communications and meeting planning assistance to the Alliance.

II. Goals and Achievements

In 2014, the Alliance held its first annual conference that offered peer-to-peer education on investment tools as well as identified a public policy platform for new investment tools. The Richmond Fed and more than seven financial institutions financially supported the initial conference and the three subsequent conferences. The four annual conferences have been held to bring new strategies and solutions to community development financing in the state. Sessions on Aeris ratings in 2017 prompted collaborative discussions of metrics for individual organizational effectiveness. The latest annual conference, held in May 2018, attracted more than 125 attendees, primarily from South Carolina, but also North Carolina, with a diverse planning team that included the Richmond Fed.

In fulfilling its mission to advance peer-to-peer education on investment tools and advocate for the implementation of new investment tools and strategies, the most recent annual conference included panels on layering community development finance tools and Opportunity Zones. A new community investment tool, Opportunity Zones are designed to drive long-term capital to eligible low-income urban and rural communities throughout the country by providing a new tax incentive for investors to re-invest their unrealized capital gains into Opportunity Funds that are dedicated to investing in Opportunity Zones designated by the chief executives of every U.S. state and territory. Opportunity Zones were introduced in the Investing in Opportunity Act (IIOA) and passed by Congress in the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017. The “Transforming Communities” program also offered participants the latest strategies, programs and resources to access capital in communities, and showed the participants how the finance deals look on the ground with three mobile workshops.

The original goals of the Alliance to establish a vehicle to easily accept and deploy capital, and to underwrite and finance debt and equity investments, remain goals for the Alliance as it looks ahead. The education and training, and the opportunity for partner networking and new connections to investors, are ongoing activities for the Alliance through its annual conference and in separate continuing education programs.

III. Financing and Nonlending Activities

The Alliance was originally created for financing activities, but determined that the scale was not sufficient in the state to pursue lending in the early phase of collaboration. Instead, the Alliance has focused on fostering collaborations between CDCs and CDFIs, and between CDFIs in North Carolina and South Carolina. Annual conferences have focused on CDFI education and building a network prepared to finance development in the state’s low- and moderate- income communities.

IV. Impact and Assessment

The Alliance’s impact on community development policy in South Carolina is most evident in its partnership with SCACED and the successful deployment of the Community Development Tax Credit.

After an inspirational program about inclusive economic prosperity that focused on impact investing and CDFI investments to help achieve social and economic impact in communities, local funders and the Alliance agreed new partnerships could be a strategic targeting tool for new investment strategies. To this end, the Alliance created a “CDFI 101” program to be delivered as a training program, via webinar and in-person, specifically targeted to foundations. The Alliance working group has focus group tested the training program to test its usefulness across different audiences and responsive to the diversity within the foundation community — ranging from small family foundations to larger foundations already making program related investments. The training tool was created by a collaboration of CDFIS, the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond and a financial institution.

V. Challenges, Opportunities and Leading Practices

The Alliance faces the challenge of potentially engaging its own financing opportunities with partner CDFIs and CDCs, and a continuing challenge to provide cutting-edge information for new financing tools for South Carolina communities. In the summer of 2018, the Alliance and SCACED drafted a set of “do no harm” guidelines for stakeholders in South Carolina to consider as planning commences for the new Opportunity Zones. Deployment of the CDFI 101 training tool will continue in the winter of 2018. Collaboration on Opportunity Zones will be ongoing including the creation of an Investment Forum in the state.

In September 2018, the northeastern region of the state suffered devastating 1,000-year floods as a result of Hurricane Florence. This same region had barely recovered from the effects of 2016’s Hurricane Matthew. Low-income rural areas are facing another redevelopment. Toward this end, early discussions about new financing for small business recovery and housing are underway. Evaluation of a previous model deployed in North Carolina for post-Hurricane Floyd (1999) redevelopment included housing counseling, application processing for state and federal programs, and repair and replacement programs at the community level that produced new Low- Income Housing Tax Credits (LIHTC) developments, new subdivisions, infrastructure repair for water, sewer and roadways, delivered by CDCs and CDFIs, based on previous successful practices.1 Assessment of developable land and potential financing of local resiliency solutions in the face of a changing natural environments are also considerations for the redevelopment model for both states.

References Cited

[1] Bonds, Jeanne Milliken and Emma Sissman, 2018, “Community Development Corporations: Diverse Practices Across North and South Carolina,” Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond Community Practice Papers, No.1.

About the Author

Jeanne Milliken Bonds, previously the Regional Community Development Senior Manager of the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond, is currently a Professor of the Practice, Impact Investment and Sustainable Finance in the Kenan-Flagler Business School and the Department of Public Policy at UNC-Chapel Hill.

Related Articles

Is North Carolina’s Attractiveness as a Migration Destination Waning?

Is North Carolina’s Attractiveness as a Migration Destination Waning?We are witnessing a re-balancing after the COVID migration surge or a fundamental shift in North Carolina’s attractiveness as a domestic and international migration magnet.White Paper by James H....

North Carolina at a Demographic Crossroad: Loss of Lives and the Impact

North Carolina at a Demographic Crossroad:Loss of Lives and the ImpactNorth Carolina’s phenomenal migration-driven population growth masks a troubling trend: high rates of death and dying prematurely which, left unchecked, can potentially derail the state’s economic...

WILL HURRICANE IAN TRIGGER CLIMATE REFUGEE MIGRATION FROM FLORIDA

Will Hurricane Ian Trigger Climate Refugee Migration from Florida?Thirteen of Florida’s counties were declared eligible for federal disaster relief following Hurricane Ian’s disastrous trek through the state (The White House, 2022). The human toll and economic impact...