WCH In the News

Analysis: Addressing Our Rural Childcare Crisis

Original article courtesy of Daily Yonder.

by James H. Johnson, Jr. and Jeanne Milliken Bonds.

Thurs. January 27, 2022

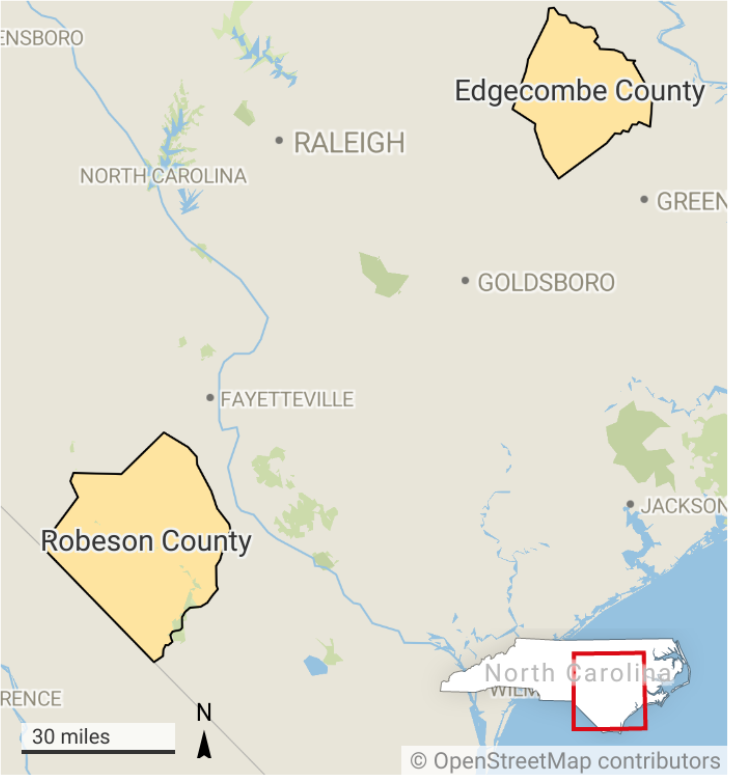

In 2020, the William R. Kenan, Jr. Charitable Trust challenged the professional schools at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill to take a deep dive into two rural counties in the eastern part of the state where unemployment, housing, healthcare, and many services including broadband and childcare leave moderate- and low-income residents behind. Both Edgecombe and Robeson counties have experienced population loss through out-migration and deaths even though both counties have community colleges and one has a constituent institution of the state university system. The challenge is to create new approaches, with UNC working as an anchor institution hand in hand with the local communities, bringing new student talent and investments to solve the challenges the communities see as their priorities.

Among the many challenges, affordable and quality childcare is a two-generation workforce—and by extension—U.S. competitiveness issue. As the U.S. Chamber of Commerce Foundation correctly notes, the nation’s childcare industry “provides essential support for the workforce of today and is vital to the development of tomorrow’s workforce.”

Yet the U.S. invests far less money in childcare and early childhood development than most other developed nations and even some developing countries. Because of inadequate investments, far too many American youth enter elementary school ill-prepared to learn—a situation that, unfortunately, has long-term negative consequences for their overall health and wellbeing. Nowhere is this more evident than in rural counties where funding for services is jeopardized by population loss and an aging population on fixed incomes unable to pay for improvements.

Pandemic Exacerbates Childcare Crisis

Prior to the Covid-19 pandemic, 51% of the U.S. population lived in a childcare desert, defined as areas where the demand far outstrips the supply of available childcare slots; existing childcare facilities (especially in-home operations) are barely sustainable financially; and, staff turnover is high because childcare workers do not earn a living wage. The research underscores wider challenges in rural childcare provision, including: fewer providers; lower numbers of staff and children to sustain operations in remote locations; inadequate transportation systems; and, difficulties recruiting and retaining staff, particularly for senior roles.

Covid-19 has cast new light on and exacerbated the nation’s childcare crisis. The mandatory shutdown of the U.S. economy idled many workers with young children, eliminating in the process their need for childcare services. This in turn forced some childcare facilities to furlough workers and close; and others to lay-off workers and close permanently. In our rural counties, low vaccination rates combined with the closures has eliminated more than 90% of the available childcare providers.

In a study we did for the N.C. Community Action Agencies focused on the effects of Covid-19, we conducted focus groups in four rural regions and one urban area of North Carolina, one respondent summed up the childcare crisis,

“And no offense to all the guys on this, but it’s [the pandemic] really been detrimental to women. The majority of the burden has been placed on not only the schooling, the childcare, the nutrition – it’s a lot. I’ve seen women cry just like, ‘I’m just so tired I don’t know what to do.’”

Low-Income Communities Hit Hardest

Most of the permanent closures have been small, in-home enterprises concentrated in minority- and low-income neighborhoods. Among these pandemic causalities, some of the businesses did not apply for financial assistance through the SBA’s Payroll Protection Program (PPP) because the paperwork was too onerous while others had major concerns about repaying the loan if it was not forgiven once the pandemic ends. Still others did not have the requisite payroll documentation, tax records, and future income projections or the required relationship with a bank to qualify for a loan under the PPP.

Larger childcare enterprises serving an upper class, predominantly white clientele in suburban communities were more likely to benefit from the PPP. Those emergency funds have enabled such facilities to either remain open throughout the crisis or reopen as the rates of exposure, hospitalizations, and deaths declined during the first wave of the pandemic.

But even the childcare enterprises that remained open or have re-opened now operate under much more stringent guidelines dictated by government-mandated lower teacher-child ratios, which substantially reduce revenue, and enhanced health and safety protocols, which sharply increase the cost of operations. This creates long- and short-term sustainability challenges for existing facilities which further threaten the viability of the nation’s childcare infrastructure—and more broadly, the current and future workforce of our nation.

Moreover, the childcare crisis is partly responsible for the Great Resignation and the workforce challenges companies are facing as they attempt to implement Return-to-Office policies and hybrid models of work environments.

Even as schools and daycares have attempted to return to in-person learning, working women have found it difficult to either return to work or maintain employment because any randomly occurring infection outbreak in a school requires mandated at-home quarantine for all exposed children. And a child in quarantine requires adult supervision, which makes maintaining a job very difficult, if not impossible, for women who are the sole or primary caregiver.

Recommendations

To address the childcare crisis, we must:

- Encourage family-friendly human-resource policies that support women having children and allow them the flexibility to provide and care for their offspring. Women—as both employees and leaders—are key to the future viability of U.S. business, nonprofit, and government enterprises.

- Strategically position—at all levels of government, in all sectors of the economy, and in the public sphere—childcare as a business imperative. Working women with young children will not be able to return to work until we invest more resources in the existing childcare infrastructure and seed the nation’s expansive childcare deserts with accessible, high quality, and affordable day care.

- Aggressively lobby the federal government to enact legislation guaranteeing all children a free early childhood education (universal pre-school). Ensuring a fantastic start for the current and future generations of talent that will have to propel our nation in the hyper-competitive global economy must be a high priority. Moreover, a universal pre-school program will make it easier for some mothers with young children to enter and others to re-enter the workforce once the pandemic is over.

- Invest in childcare business incubators and accelerators for existing and aspiring childcare entrepreneurs. The American Rescue Plan allocates $39 billion to states to expand and improve childcare in the U.S. Additional dollars may be forthcoming if Congress enacts President Biden’s Build Back Better plan. In addition to providing children in their care a world class early childhood experience, childcare entrepreneurs, especially those small in-home operations, must leverage sound business, managerial, and record keeping principles and practices in their daily operations to ensure the future viability and sustainability of their enterprises.

- Advocate for more and better continuing education programs for childcare workers. Strengthening their educational background and training will enable them to move away from providing basic childcare to rendering culturally- and age-appropriate child development services—an important step given the increasing diversity of U.S. births. This will go a long way toward ensuring all children enter elementary school ready and excited to learn, especially children of color from low-wealth families and economically marginalized communities.

- Engage in the ongoing livable wage campaign for the nation’s childcare workforce. Sound early childhood development for the next generation of talent is honorable work and should be compensated accordingly.

To achieve these outcomes, we must design and beta-test best practice interventions for communities. With support from the William R Kenan, Jr. Charitable Trust, we are implementing such as demonstration project in our two North Carolina rural counties through our Whole Community Health Initiative. The three-pronged strategy includes a Child Care Business Accelerator to equip existing and aspiring childcare entrepreneurs with business acumen and skills; a Childhood Equity Fellows Program to train childcare workers in the best “whole community health” child development practices; and a Child Care Wage Accelerator that will use cash transfers as a means of compensating childcare workers and addressing the low wage conundrum.

The goal is to demonstrate how such a dynamic ecosystem of interventions in two rural counties will grow sustainable businesses and jobs; enhance marginalized female labor force participation; and increase access to quality childcare in former childcare deserts. If this two-county demonstration proves successful, we devise a state-wide rollout strategy and leverage government, philanthropic, and corporate support to ensure that every child moving forward has an equitable opportunity to participate in and benefit from North Carolina’s booming economy.

Other News

Mass Migration: Why are people moving south?

Mass Migration: Why are people moving south?Virginia’s demographics are changing. Jeanne Milliken Bonds, public policy professor at UNC Kenan-Flagler Business School explains the shifts. Home | Publications | Mass Migration: Why are people moving south?...

The EIDC Economic Development Journal – Fall 2023

WCH In the NewsThe EIDC Economic Development Journal - Fall 2023 International Economic Development Council1275 K Street, NW, Suite 300 • Washington, DC 20005 • www.iedconline.orgChair: Jonas Peterson, CEcDPresident & CEO: Nathan OhleEditor: Jenny Murphy.November...

The painful pandemic lessons Mandy Cohen carries to the CDC

The painful pandemic lessons Mandy Cohen carries to the CDC"North Carolina initially failed to prioritize testing for people who were exposed to #COVID19 because of where they live or work." - Jeanne Milliken Bonds, Professor of Social Impact Investing at the...