Establishing Reputational Equity for the Nursing Profession

The Covid-19 pandemic magnified diversity and inclusion challenges in the nursing profession in the United States.

Journal Article by James H. Johnson Jr., Ph.D, Jeanne Milliken Bonds, MPA

Kenan-Flagler Business School UNC-Chapel Hill

Rumay Alexander Clinical Professor Adult Health, Health, and Social Justice

UNC-Chapel Hill

January 2021

Home | Publications | Establishing Reputational Equity for the Nursing Profession

The nursing profession in the United States was experiencing a labor shortage and facing diversity and inclusion challenges prior to the Covid-19 pandemic [1-5]. Magnifying these problems, the nation’s population was shifting–geographically and demographically [6,7]. This resulted in changes in both where nurses are needed in the health care system and the nursing skill set required to address health care needs of a far more diverse clientele of patients—in terms of race, ethnicity, sex, gender identity, age, living arrangements, socio-economic status, and spoken language [1].

The COVID-19 pandemic has complicated matters by exacerbating the nursing shortage and further highlighting diversity challenges within the nursing profession and the U.S. health care system more generally [8,9]. These problems are rooted in two critical facets of the current crisis.

The first critical facet is the way in which the COVID-19 pandemic has evolved over time [10,11]. Initially, the major coronavirus hot spots were concentrated in New York City and other major urban centers. Then, the hot spots shifted to the Sunbelt. Most recently, the virus has spread rapidly in sparsely populated states in the upper Midwest and Mountain regions as well as diverse states like California— causing in each instance major shifts in demand for nurses and other health care workers.

Further complicating matters, in response to these successive waves of spread, some residents—dubbed coronavirus pandemic refugees–have fled coronavirus hot spots, often relocating to smaller, less densely or more sparsely settled communities in the suburbs, exurbs, and small towns, areas perceived to be safer because practicing social distancing is easier [12]. A significant share of the pandemic refugees appears to be wealthy individuals voting with their feet to protect themselves and their loved ones from the spread of the deadly virus.

However, the shift to remote work, implemented in some industries to reduce possible exposure to the deadly virus, created the impetus for some middle- and moderateincome homeowners and renters—mainly millennials and families with young children—also to flee coronavirus hot spots, especially high cost of living urban centers like New York, Seattle, San Francisco, and Los Angeles. This has led in some instances to the emergence of so-called Zoom towns in amenity rich, exurban and rural areas (especially in the western U.S.) where the health care systems and other public services may not be adequate to accommodate the influx of newcomers [13,14].

The second critical facet is the disparate impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on older adults and people of color— individuals who are especially vulnerable because their immune systems and overall wellbeing have been severely comprised by the social determinants of health [15,16]. Effective care of these individuals requires nurses and other health care staff with specific language fluencies, cultural competencies, and specialty care skills that are often in limited supply, especially in rural communities and economically distressed urban areas affected by the pandemic.

Health-care systems across the U.S. have employed multiple strategies to address their COVID-19 pandemicinduced nursing shortages and other staffing needs [8,9]. Action steps include extending shift hours of existing nurses, recruiting retired and travel nurses, and drawing on military medical and federal agency reinforcements. Yet, the personnel challenges remain as successive waves of the deadly virus decimate the existing nursing workforce.

Nurses on the frontlines of Covid-19 pandemic are intensely committed to their profession and highly motivated to serve in the current crisis. However, forces beyond their control are driving staff turnover. They include [9]:

- Mental health challenges and burnout due daily exposure to coronavirus-related trauma and loss of life;

- Personal exposure to the virus requiring quarantine or hospitalization leading–in some instances–to death; and

- Forced resignations to care for exposed family members or children requiring home schooling or home childcare due to the Covid-19 pandemic.

These problems are especially acute for health-care systems in rural communities. Such systems typically do not have the resources to recruit travel nurses and, even if they did, may not be attractive work destinations for nurses in this sector of the profession [8]. Moreover, for the existing nursing workforce, these communities usually lack networks of caregiving institutional supports that are typically more readily available in wealthier urban and suburban communities.

Elsewhere, we have highlighted nine specific steps the nursing profession must take to address the nursing shortage generally [1]. Here we focus on two recommended actions as specific responses to staffing and diversity challenges that the Covid-19 pandemic has presented.

Organizational leaders and stakeholders in the nursing profession ecosystem must first develop a keen understanding and appreciation of how disruptive demographics are transforming and will continue to transform the nation’s workforce in the years ahead [6,7]. Immigrants and native born people of color are changing the complexion of the U.S. workforce–popularly referred to as the “browning” of America—at the same time that a large segment of the U.S. native born, predominantly white population is aging out of the workforce—popularly referred to as the “greying” of America [6,7].

Concerns about the browning and greying of America are polarizing issues in our nation’s current political and policy discourse [17]. Political land mines notwithstanding [18], key stakeholders in the nursing profession must recognize and embrace, as a core business strategy, the pivotal role that people of color will play in the profession’s workforce of the future [1,7].

Second, to compete successfully, especially given shifting workforce dynamics, organizational leaders will have to demonstrate commitment to dismantling systemic racism in the nursing profession ecosystem [2,15]. At the same time, they must embrace the core principles of Diversity, Equity, Inclusion and Belonging (DEIB) in talent recruitment, development, retention, and promotion, creating in the process what Johnson and Bonds [19] refer to as reputational equity for the nursing profession.

Specifically, to create reputational equity, the nursing leadership must undertake a comprehensive DEIB audit of the entire nursing profession ecosystem. That is, they must critically review and evaluate policies, procedures, and practices that govern the day-to-day operations of professional schools that train and produce the nursing workforce. The same must be done for the various components the U.S. health-care system that relies on the talent the nursing education, training, and certifying systems produce.

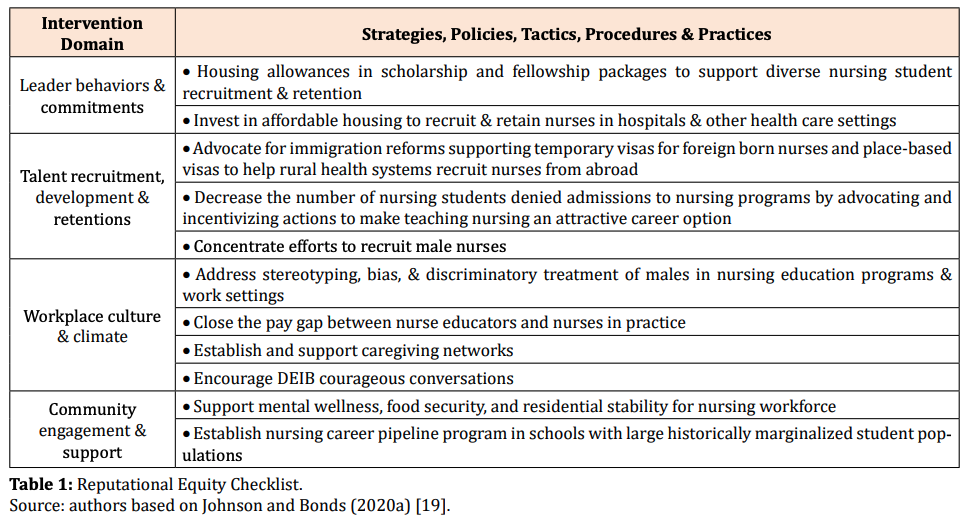

This ecosystem-wide diagnostic assessment, as we have shown elsewhere [1], will identify regulatory, administrative, and financial constraints and barriers that undergird the nursing shortage and inequities in nursing education, training, and certification, as well as working conditions in health care settings. Key stakeholders in the nursing profession should use the checklist of the evidenced-based strategies, policies, tactics, and procedures for developing reputational equity as a guide to fix problems uncovered in the DEIB organizational audit (Table 1) [19].

As the table below shows (left panel), the checklist includes four intervention domains. Based on research on corporate reputational equity, we have populated the table (right panel) with examples of specific implementable strategies, policies, tactics, procedures and practices that address the labor shortage and DIEB issues in the nursing profession.

We believe a fully executed DEIB audit using the reputational equity checklist will enable the nursing profession to “continuously recruit, train, employ, nurture, and retain a diverse workforce with demonstrated cultural competencies to care for an increasingly more diverse client base” [19]. At the same time, it will enhance the ability of health-care entities, nationally and internationally, to be better prepared to ensure a workforce that meets the needs of communities when confronted with the next major health crisis.

About the Authors

James H. Johnson, Jr. is the William Rand Kenan, Jr. Distinguished Professor of Strategy and Entrepreneurship in the Kenan-Flagler Business School and Director of the Urban Investment Strategies Center in the Frank Hawkins Kenan Institute of Private Enterprise at UNC-Chapel Hill.

Jeanne Milliken Bonds is a Professor of the Practice, Impact Investment and Sustainable Finance in the Kenan-Flagler Business School and the Department of Public Policy at UNC-Chapel Hill.

Rumay Alexander is a Clinical Professor of Adult Health, Health, and Social Justice at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

References Cited

1. Alexander GR, Johnson JH (2021) Disruptive Demographics—Their Effects on Nursing Demand, Supply and Academic Preparation, Nursing Administration Quarterly 45(1): 58-64.

2. Carter BM, Alexander GR (2021) Entrenched White Supremacy in Nursing Education Administrative Structures. Creative Nursing 27(1).

3. Registered Nursing (2020) The States with the Largest Nursing Shortages.

4. Galehouse M (2019) What’s Behind the Nursing Shortage? How Can we Fix It? TMC Pulse.

5. Wojciechowski M (2017) Challenges Facing Nursing Students Today, Minority Nurse.

6. Johnson James H, Parnell Allan M (2016) The Challenges and Opportunities of the American Demographic Shift. Generations 40.

7. Johnson James H, Parnell Allan M (2019) Seismic Shifts, Business Officer.

8. Hawryluk M, Bichell RE (2020) Need a COVID-19 Nurse? That’ll Be $8,000 a Week, Kaiser Health News.

9. McLeron LM (2020) COVID-Related Nursing Shortages Hit Hospitals Nationwide, CIDRAP News.

10. Jones B, Kiley J (2020) The Changing Geography of COVID-19 in the U.S., Pew Research Center, U.S. Politics & Policy.

11. Kuchler T, Russel D, Stroebel J (2020) The Geographic Spread of COVID-19 Correlates with the Structure of Social Networks as Measured by Facebook, NBER Working Paper 26990.

12. Johnson JH (2021) Coronavirus Pandemic Refugees and the Future of American Cities. Urban Studies and Public Administration 4(1): 1-22.

13. Stoler P, Rumore D, Romaniello L, Levine Z (2020) Planning and Development Challenges in Western Gateway Communities. Journal of the American Planning Association 87(1): 21-33.

14. Smith L (2020) Zoom Towns are Exploding in the West, Fast Company.

15. Garcia MA, Homan PA, García C, Brown TH (2020) The Color of COVID-19: Structural Racism and the Disproportionate Impact of the Pandemic on Older Black and Latinx Adults. Journal of Gerontology Series B.

16. Del Rio Carlos (2020) COVID-19 and Its Disproportionate Impact on Racial and Ethnic Minorities in the United States. Contagion 5(4).

17. CMS (2020) President Trump’s Executive Orders on Immigration and Refugees, Center for Migration Studies.

18. Johnson James H, Bonds JM (2020b) Scapegoating Immigrants in the COVID-19 Pandemic, Frank Hawkins Kenan Institute of Private Enterprise White Paper 2, pp: 1-11.

19. Johnson James H, Bonds JM (2020a) Does Your Firm Have Reputational Equity? Journal of Business and Social Science Review 1(11): 1-9.

Related Articles

Is North Carolina’s Attractiveness as a Migration Destination Waning?

Is North Carolina’s Attractiveness as a Migration Destination Waning?We are witnessing a re-balancing after the COVID migration surge or a fundamental shift in North Carolina’s attractiveness as a domestic and international migration magnet.White Paper by James H....

North Carolina at a Demographic Crossroad: Loss of Lives and the Impact

North Carolina at a Demographic Crossroad:Loss of Lives and the ImpactNorth Carolina’s phenomenal migration-driven population growth masks a troubling trend: high rates of death and dying prematurely which, left unchecked, can potentially derail the state’s economic...

WILL HURRICANE IAN TRIGGER CLIMATE REFUGEE MIGRATION FROM FLORIDA

Will Hurricane Ian Trigger Climate Refugee Migration from Florida?Thirteen of Florida’s counties were declared eligible for federal disaster relief following Hurricane Ian’s disastrous trek through the state (The White House, 2022). The human toll and economic impact...