Pay for Success: How Emerging Finance Tools Are Supporting Workforce Development

Pay for Success (PFS) is a public policy tool that may be used in the workforce development sector to test new programs guided by predetermined outcomes for a target population or a community. PFS is a contractual arrangement that hopefully will lead to long-term positive change for both the individuals and communities.

Special Topic Brief by Jeanne Milliken Bonds, MPA

Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond

2019

Home | Publications | Pay for Success: How Emerging Finance Tools are Supporting Workforce Development

Topic Overview

Pay for Success (PFS) is a public policy tool that may be used in the workforce development sector to test new programs guided by predetermined outcomes for a target population or a community. PFS is a contractual arrangement that ties payment for delivery of services to specific, measurable outcomes. Through the contract, it ensures quality and effective services that hopefully will lead to long-term positive change for both the individuals and communities. For example, outcomes may be measured by participants in job training programs finding and sustaining employment, and ultimately experiencing wage increases.

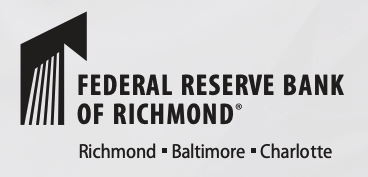

As Figure 1 indicates, in a PFS contract, the payor for outcomes is usually government (local, state, or federal). In this case, the government entity enters into an agreement with the investors to pay for services with an agreed-upon result, and provides funding to the investors if and when the services are delivered and the result is achieved. Investors may be commercial, philanthropic, or community development organizations that provide the capital to designated service providers. An independent evaluator determines at the end of the contract whether the agreed-upon outcomes have been met. Because evaluation results determine whether or not investors are repaid and may contribute to evidence on the effectiveness of the intervention, early PFS projects in the United States have included rigorous evaluation methods.

Whereas governments typically fund pilot programs up-front to test new ideas and outcomes, PFS only funds services or projects that bring about results consented to in the contract. Because payment is not made until the specific outcome is achieved, taxpayers no longer bear the risk of paying for pilot programs or other services that may or may not be effective.

Over the past few years, there has been an increase in substantive commitments from the philanthropic community and the federal government, enabling state and local governments to partner with high-performing service providers with access to private investments. As shown in Figure 2, since 2011, more than 20 projects have launched and nearly 50 more are in development.1 Private investors create financial and social impact incentives for service providers to deliver the outcomes that capitalize the highest return on any taxpayer investments. As is the case in any financing scenario, different funders tolerate varying levels of risk, such that some may be less apt to finance projects that target the most challenging social issues. Research on the challenge being addressed and rigorous evaluations throughout the process deter practices that eliminate hardest-to-serve populations from the equation.

The Pay for Success Ecosystem

While PFS is a promising policy tool to address some of the most persistent issues communities face, the amount of time and resources to launch a project is extensive. All parties must first reach a consensus on the best measures of outcomes, and then it can take years to achieve results. There are several examples of nonprofits and academia working in partnership with community organizations to adopt the PFS model in their communities.

Three U.S. universities have created programs to support and streamline the process for PFS projects. The Harvard Kennedy School Government Performance Lab provides technical assistance to government entities on the design and implementation of projects with a focus on next stage development. Harvard’s Social Impact Bond [2] Technical Assistance Lab, established in 2011 with support from the Rockefeller Foundation, was the precursor to the current PFS model. The Social Impact Bond Technical Assistance Lab helped Massachusetts and New York become the first two states to use the PFS model as a public policy tool. The Government Performance Lab also worked with the South Carolina Department of Health and Human Services to address lowering rates of preterm births and child injuries. The state agency used Medicaid waivers to provide nurse home-visiting services to lowincome, first-time mothers from the second trimester of pregnancy until their child’s second birthday. [3]

At the University of Utah’s David Eccles School of Business, the Sorenson Impact Center is a “think-and-do tank” that engages social impact financing, connects research with programmatic design, as well as executes and evaluates social impact projects. Sorenson provides a competitive grants program. In September 2018, the Sorenson Impact Center in partnership with Social Finance, Inc. [4] awarded a PFS transaction structure contract to Philadelphia Works, Inc. to develop a publicprivate partnership for skills training for low-wage workers in jobs at risk of automation in order to move the workers into technical, middle-skill jobs. [5]

The University of Virginia Pay for Success Lab launched in September 2015 to identify promising PFS projects and refer them to advisory firms for implementation. Teams of students work under the direction of a staff director. [6] Also in Virginia, a PFS Council formed in 2013 with business and industry partners, as well as human service and government organizations, to initiate a model for early childhood programs. Third Sector Capital Partners, Inc., the University of Virginia Pay for Success Lab, and other organizations are working together to determine project feasibility.

In addition to academia, a nonprofit, the Non-Profit Finance Fund, is a Learning Hub site in partnership with the PFS community that serves as a central resource where individuals can share ideas, learn from one another’s experiences, and collaborate in the search for best practices. Organizations and communities interested in learning about ongoing PFS projects can receive updates via their web portal. Currently, the site serves as the national repository for PFS strategies and research.

Public Sector Support for Workforce Development Projects

Early childhood and other child educationfocused programs offer excellent testing grounds for PFS strategies. PFS removes the risk of paying for services that are ineffective, and may ultimately lead to higher returns on taxpayer investment in education. As a result, the U.S. Department of Education (ED) manages a competitive process for PFS projects, including preschool for three- and four-year olds; services for younger, disabled children; dual-language learning; and new and expanded career and technical education for underserved youth. [7]

As federal funding for workforce development has trended downward over the past 20 years, the workforce development community at large has sought new and effective training and development opportunities to respond to shifting industry and skill demand. More often than not, programs lack evidence for successful outcomes and long-term effectiveness remains uncertain. PFS is one pathway to provide innovative and outcomes-oriented financing options.

When the Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act (WIOA) was reauthorized in 2014, PFS emerged as an eligible use of formula funding. Two federal agencies led efforts to deploy PFS. The U.S. Department of Labor (DOL) funded the first PFS workforce development projects in New York and Massachusetts the year prior to WIOA for training and employment services. One of the programs funded by PFS in the DOL, My Brother’s Keeper (MBK), was launched to address “persistent opportunity gaps faced by boys and young men of color and ensure that all young people can reach their full potential.” [8] MBK targets various milestones focused on children entering school ready to learn. [9]

The second federal agency, ED, funded Social Finance, Inc. and Jobs for the Future [10] to support the development of PFS K–12 career and technical education opportunities. ED also funded the American Institutes for Research to study evidencebased interventions for early learning dual language models and to identify how PFS could help improve outcomes for children learning English as a second language. [11]

A U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) 2015 report reviewed 10 PFS projects to assess risk, as well as the design and implementation of the contracts to ensure entities involved are not incentivized to address less challenging projects, resulting in higher success rates and skewed evidence. GAO recommended that federal agencies could collaborate on PFS projects, which would help build a body of evidence on the effectiveness of specific PFS strategies. The GAO report was instrumental in informing policymakers of how projects are structured and what potential benefits may accrue, as well as how the federal government can be involved. The GAO recommendations included the need for leading practices and collaboration among federal agencies. [12]

The GAO report was supportive of PFS methodology as a financing method, and may certainly be considered a catalyst for the Social Impact Partnerships to Pay for Results Act of 2018 (SIPPRA), enacted in February 2018, which generated a $100 million U.S. Department of the Treasury-controlled fund for state and local PFS projects. The federal government acts as the end payor for projects undertaken. SIPPRA creates a nine-member standing Commission on Social Impact Partnership that will work with Treasury to review PFS funding applications. The first requests for proposals were in February 2019 [13] for employment and workforce development, high school graduation, early childhood education, and resilience planning for weather-related events in cities and rural areas. Funding for projects, feasibility studies, and evaluations will be available for 10 years after the date of enactment so that state and local governments may propose projects with outcome goals over a 10-year time period. [14]

With the passage of SIPPRA in 2018, the federal government has renewed support for PFS and there is new momentum for this financing option. State and local governments have the opportunity to identify programs that could produce the highest federal costs savings and reduce long-term expenditures. It is therefore more important than ever to undergo rigorous evaluations to ensure PFS projects are feasible, undertake challenging social issues, achieve maximum impact, and document the results. [15]

Current Challenges

There remain challenges in implementing the PFS model for workforce development projects. For one, research shows that while PFS has had a positive impact on educational outcomes, labor market outcomes are mixed, with increased earnings in some states and less significant changes in other states. [16]

In 2014, the Joyce Foundation published learnings from a 2013 summit on PFS activity in the workforce field, following DOL’s June 2012 Solicitation for Grant Applications. The foundation sought to learn from national stakeholder teams from across the country who participated in the grant applications about the state of workforce-related PFS projects and current opportunities, challenges, and needs. [17]

The summit conversation provided insight about the challenges of workforce-related project interventions and the diversity of projects such as stage-based programming for at-risk young men, mentorships for families on public assistance, career pathways education and job training support for low-income adults on public assistance, life skills training, and social enterprise employment. Each project aimed to increase employment for target populations and was based on multiple years of implementation by the service provider, where evidence exists. Questions remain as to whether or not workforce stakeholders will be able to use the PFS model to support innovation and risk-taking in interventions based on the projects to date.

Summit participants discussed the two aforementioned DOL programs in Massachusetts and New York, which both had strong internal government champions, as well as resources and staff support from Harvard University’s Social Impact Bond Technical Assistance Lab. Both programs had strong performance data and third-party evidence and “a dedicated intermediary organization—Social Finance in NY and Third Sector Capital Partners in MA—able to provide financial structuring and modeling expertise, investor management, contract management, project management, and other stakeholder negotiation services.” [18] The services helped support innovation and risk. Both models achieved recidivism reduction and employment target goals. Participants in the summit highlighted that the recidivism-cost savings are easier to quantify in the context of a PFS transaction than savings related to workforce development measures like job placement, which remain a challenge.

Discussion of other PFS challenges at the summit included how to analyze complex data to measure outcomes; find sufficient capacity among service providers, government, and intermediaries; create flexibility in PFS structures; and build collective support from philanthropy and government entities. While PFS is still considered to be an emerging model for financing complex social issues, similar challenges are expected to remain for the projects submitted under SIPPRA. Figure 3 provides a structure for determining when PFS makes sense as a financing tool.

Listening Session Perspectives

During various stakeholder roundtable listening sessions in North Carolina and Virginia, community development, academic, and investor participants shared their perspectives on the flexibility of WIOA approaches with respect to PFS. Individuals also spoke about the small number of universities engaged to help with PFS projects, as well as the need to “train the trainer” and enlist more university expertise and assistance. Concerns were also raised about how to best relay the knowledge about the PFS process from philanthropy and government to new participants.

Common among stakeholders was the desire to learn about SIPPRA projects in real time. Roundtable participants suggested a platform with information about past PFS projects as well as current SIPPRA models, from which stakeholders could learn and implement promising practices.

Promising Strategies

The Northern Virginia WIOA Youth Program is a PFS targeting opportunity youth, defined as 16- to 24-year-olds who are neither in school nor working. The challenge being addressed is that once a youth ages out of foster care, taxpayers will pay approximately $300,000 over that young person’s lifetime through public assistance, incarceration, and lost wage costs. If these youth are redirected to education, training, and gainful employment, benefits accrue to the individuals and taxpayers. [19]

The SkillSource Group is a nonprofit organization of the Northern Virginia Workforce Development Board (NVWDB), serving Northern Virginia employers, incumbent workers, and job seekers with job placement, training, and educational services. The group’s six One-Stop Employment Centers serve 64,000 clients each year. SkillSource works with Fairfax County, the One-Stop Operator for Northern Virginia Workforce Area #11, including Fairfax, Loudoun, and Prince William counties, and the cities of Manassas, Manassas Park, Fairfax, and Falls Church. In 2015, SkillSource applied for technical assistance from Third Sector Capital Partners to explore the intersection of PFS and WIOA funding for improved outcomes for youth.

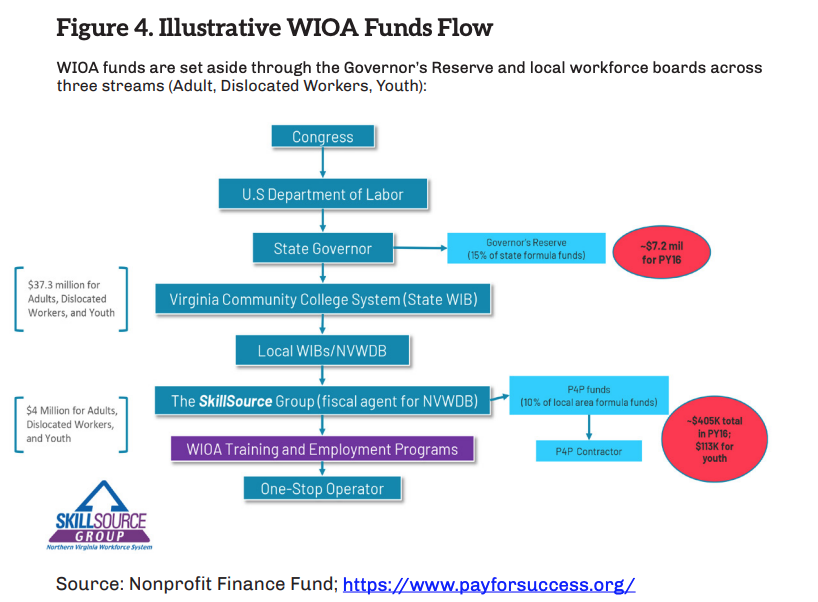

As part of the PFS opportunity youth project, the Northern Virginia Team Independence Initiative, a partnership between SkillSource, Fairfax County Division for Family Services (DFS), and social service and justice organizations across Northern Virginia, has created a new mobile unit, meeting young adults at nontraditional locations. The contract is designed to increase the number of young adults engaged in education and employment programs and to improve skills development and employment outcomes for economically disadvantaged foster care and justice-involved young adults using the Northern Virginia Workforce System. By leveraging new provisions in the 2014 WIOA (see Figure 4), the project will attempt to serve 100 out-of-school and unemployed foster care and justice-involved young adults through mobile outreach and enrollment in the community, as well as targeted case management focusing on hard-to-reach young adults in the region. Pay for performance, or bonus payments, can be earned by Fairfax County DFS—one bonus for each successful outcome achieved over the course of the project. Measures being tracked for the participants are skills gained during programming; placement in training, employment, or education six months and a year after exit; and attainment of a degree or certificate within a year after exit.

In 2015, eight young adults were enrolled, and in 2017, 25 were enrolled. As of March 2018, 67 young adults participate in the Northern Virginia program: 63 percent of participants are out of school; 76 percent are basic skills deficient; 47 percent have a documented disability; 15 percent engaged with the juvenile justice system; and 6 percent are in foster care. [20]

Conclusion

While PFS for workforce development financing is a promising practice, it does not come without challenges. With respect to projects focused on reducing recidivism, tracking in real time is not possible and detailed case level information is not easy to obtain. Metrics like long-term employment status are particularly difficult to follow.

There are also challenges in creating performance targets that are feasible but that also account for lasting impact. For example, if initial job placement is an agreed-upon program outcome, then a payment related to job placement would indicate success. However, participants may not actually remain employed beyond a short time period, necessitating goals around retention with longer-term benchmarks. These nuances around target outcomes indicate that time dedicated to performance management can be extensive and should be accounted for in the budget.

The growth in PFS projects has the potential to increase opportunities to finance workforce programs for both youth and adults. More recent federal and philanthropic support can help to grow and improve upon this model around the country. Yet, there remains limited expertise through entities such as academic labs to support project design. More resources are needed to take on the complex and dynamic challenges of education and training in relation to how to most effectively structure, finance, and implement PFS models.

Acknowledgments

This special topic brief is part of a series and the result of a collaborative effort across the community development departments in the Federal Reserve System. The Federal Reserve community development function thanks the participants of the 2018 regional listening sessions, who generously shared their time, knowledge, and insights to inform this research. We would also like to acknowledge individuals across the Fed System responsible for hosting the 2018 regional listening sessions and/or writing special topic briefs.

The views expressed in this special topic brief are those of the listening session participants, as summarized by the authors, as well as the author’s own insights, and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Federal Reserve System.

Methodology

In 2017, the community development departments at each of the 12 Federal Reserve Banks organized regional meetings at locations around the country with nearly 1,000 workforce development leaders to confer on the status of the nation’s workforce development system and the challenges it faces. The community development team at the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia gathered and analyzed the information from those meetings, and it subsequently published Investing in America’s Workforce: Report on Workforce Development Needs and Opportunities.

In 2018, the Federal Reserve’s community development departments conducted a second series of regional meetings with stakeholders across public, private, and nonprofit sectors. The meetings focused on several workforce-related topics that impact communities, which originated from themes captured in the 2017 report. A series of special topic briefs were created based on regional meetings and community development research interests. Briefs include research and insights from workforce development organizations, experts, and community development staff.

About the Initiative

Investing in America’s Workforce is a Federal Reserve System initiative in collaboration with the John J. Heldrich Center for Workforce Development at Rutgers University, the Ray Marshall Center for the Study of Human Resources at the University of Texas at Austin, and the W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research. Led by the community development function of the Federal Reserve System, the initiative aims to reframe and reimagine workforce development efforts as investments that can lead to scalable solutions and measurable outcomes. Components of the initiative to further this goal include:

- A series of listening sessions and subsequent report and special topic briefs aimed at gathering and analyzing information and ideas from people who work at the intersection of workforce training, recruiting, and finance.

- A national conference in Austin, Texas, in October 2017, where over 300 attendees discussed promising approaches to workforce development.

- A three-volume book that offers research, best practices, and resources on workforce development from a wide range of experts in various fields.

- A training curriculum for Community Reinvestment Act bank examiners on qualifying workforce investments under new Interagency Q&A clarifications for the regulation.

For more information about the initiative, and to read chapters from the three-volume book and other special topic briefs, please visit www.investinwork.org.

About the Author

Jeanne Milliken Bonds, formerly the Regional Community Development Team Leader, is now a Professor of the Practice, Impact Investment and Sustainable Finance in the Kenan-Flagler Business School and the Department of Public Policy at UNC-Chapel Hill.

References Cited

[1] Croan, Jerry. “Planning and Conducting a Feasibility Study” (presentation, Pay for Success Discussion Meeting, Cary, North Carolina, September 23, 2016). https://www.richmondfed.org/community_development/community_highlights/2016/20161018_north_carolina_cary.

[2] Social Impact Bonds is another way to describe Pay for Success financing. Other names include pay for success bonds, social benefit bonds, and social bonds.

[3] Government Performance Lab. “South Carolina Nurse Family Partnership Pay for Success.” Harvard Kennedy School. https://govlab.hks. harvard.edu/south-carolina-nurse-family-partnership-pay-success.

[4] Social Finance is a nonprofit organization that moves capital to social progress through social impact financing by managing public-private partnerships.

[5] The Sorensen Impact Center. 2018. “The Sorenson Impact Center and Social Finance Announce Awardee of Pay for Success Structuring Grant.” University of Utah’s David Eccles School of Business. https://sorensonimpact.com/pfs-structuring-grant-awardee-press-release.

[6] Giovannitti, Jen and Joshua Ogburn. 2018. “Growing the Pipeline of Payfor-Success Projects,” Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond Community Practice Paper. https://www.richmondfed.org/publications/community_development/practice_papers/2018/practice_papers_2018_no2.

[7] U.S. Department of Education. 2016. “Pay for Success (PFS).” https:// www.ed.gov/category/keyword/pay-success-pfs https://www.ed.gov/ category/keyword/pay-success-pfs.

[8] The White House. “My Brother’s Keeper 2016 Progress Report: Two Years of Expanding Opportunity and Creating Pathways to Success.” https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/sites/whitehouse.gov/files/ images/MBK-2016-Progress-Report.pdf.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Jobs for the Future is a national nonprofit organization working in education and workforce systems to analyze issues and design strategies.

[11] O’Connor, Brendan. 2018. “Pay for Success Legislation Moves Government to Fund What Works.” The Urban Resilience Project, published in collaboration with the Island Press Urban Resilience Project, supported by the Kresge Foundation and the JPB Foundation. Originally published March 28, 2018 in Morning Consult. https://medium.com/@ UrbanResilience/pay-for-success-legislation-moves-government-tofund-what-works-e140cb05abbb.

[12] U.S. Government Accountability Office. 2015. “PAY FOR SUCCESS: Collaboration among Federal Agencies Would be Helpful as Governments Explore New Financing Mechanisms.” GAO-15-646. https://www.gao. gov/products/GAO-15-646.

[13] U.S. Department of Treasury. “SIPPRA – Pay for Results.” https://home. treasury.gov/services/social-impact-partnerships/sippra-pay-forresults.

[14] “S.963, Social Impact Partnerships to Pay for Results Act,” 115th Congress, 2017–2018. https://www.congress.gov/bill/115th-congress/ senate-bill/963.

[15] See endnote 12 (U.S. Government Accountability Office 2015).

[16] Milner, Justin, Matthew Eldridge, Kelly Walsh, John Roman. 2016. “Research Report: Urban Institute Project Assessment Tool.” The Urban Institute. https://www.urban.org/research/publication/pay-success-project-assessment-tool.

[17] Nonprofit Finance Fund and the Joyce Foundation. 2014. “Pay for Success in Workforce Development: What We’ve Learned and What’s Next.” https://payforsuccess.org/sites/default/files/resource-files/PFS%20 in%20Workforce%20Development.pdf

[18] Ibid.

[19] Annie E. Casey Foundation. 2013. “Aging Out of Foster Care in America.” Jim Casey Youth Opportunities Initiative. https://www.aecf.org/resources/aging-out-of-foster-care-in-america/.

[20] Croan, Jerry. “Planning and Conducting a Feasibility Study” (presentation, Pay for Success Discussion Meeting, Cary, North Carolina, September 23, 2016). https://www.richmondfed.org/community_development/community_highlights/2016/20161018_north_carolina_cary. Revised 2018.

Related Articles

Is North Carolina’s Attractiveness as a Migration Destination Waning?

Is North Carolina’s Attractiveness as a Migration Destination Waning?We are witnessing a re-balancing after the COVID migration surge or a fundamental shift in North Carolina’s attractiveness as a domestic and international migration magnet.White Paper by James H....

North Carolina at a Demographic Crossroad: Loss of Lives and the Impact

North Carolina at a Demographic Crossroad:Loss of Lives and the ImpactNorth Carolina’s phenomenal migration-driven population growth masks a troubling trend: high rates of death and dying prematurely which, left unchecked, can potentially derail the state’s economic...

WILL HURRICANE IAN TRIGGER CLIMATE REFUGEE MIGRATION FROM FLORIDA

Will Hurricane Ian Trigger Climate Refugee Migration from Florida?Thirteen of Florida’s counties were declared eligible for federal disaster relief following Hurricane Ian’s disastrous trek through the state (The White House, 2022). The human toll and economic impact...